Decision Support Tool Overview

| Site: | Pukunui Demo Site |

| Course: | tool |

| Book: | Decision Support Tool Overview |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 14 March 2026, 11:16 AM |

Description

This online book resource outlines the Decision Support Tool. You can use the navigation to access the different chapters.

1. Introduction and Purpose

Collaborations and other forms of inter-agency working are important mechanisms for addressing complex social problems and creating new and innovative service delivery approaches. Collaboration is not a business as usual approach: it demands/requires considerable investments of time, resources and commitment, as well as an appetite for large scale change and risk, including risk of failure.

Yet, despite these restrictions collaboration is often presented as the ‘one best way’ or the ‘holy grail’ for integration/working together (Keast et al, 2003, 2997; 2011; Bryson, Crosby and Middleton, 2006; O’Flynn, 2009; 2011), ignoring the opportunities offered by a wider array of integration approaches.

A growing body of research and practice has illustrated that success in collaboration is the result of highly strategic and deliberate decision-making and action, clustered around – clarity of purpose (matching model to purpose), partner composition and relational strengths, the contribution and value add, and new or expanded management and leadership capabilities/competencies (and context). As such this tool is designed to offer alternative models of networking, in order to allow organisations to direct their efforts according to their immediate capabilities and purpose.

This collaboration decision support tool has been designed as a resource to aid organisations considering entering into or forming collaborations to (a) help to determine if collaboration is the most appropriate model, (b) assess current capacity and capability to undertake collaborative action, and (c) offer strategies and resources with which to go forward. It is informed by a strong evidence base drawn from research and practice.

Using the decision support tool will help participating organisations to:

- develop a clearer understanding of the range of purposes of collaborations

- reflect on the partnerships they have established

- focus on ways to strengthen new and existing partnerships by engaging in discussion about issues and ways forward

Robyn Keast

Dan Chamberlain

Southern Cross University, 2014

2. About the Tool

The tool is designed to provide a structured process to inform decision-making related to joint working/collaboration. It sets out a suite of key questions to guide and facilitate discussion with internal organisational members as well as between other agencies in the sector.

Wherever possible, the activities should be completed by participating partners as a group. The discussion involved in working through the activities will help to strengthen the partnership by clarifying ideas and different perspectives. In some cases, it may indicate that the partnership is not working as intended.

Where a lead agency has initiated or is coordinating the partnership, they would normally assume responsibility for facilitating the three activities. Completing the activities will take a number of hours because there will be a variety of perspectives among the partners and different evidence will be cited as a way of substantiating the views people hold. The various partners need time to reflect on the partnership and how it is working. The discussion that occurs around completing the tasks will contribute to the partnership because ideas, expectations and any tensions can be aired and clarified.

This tool is intended to serve as both an assessment of your current ability to collaborate and as guide to your future collaborative practices. The resources required for successful collaborations are cumulative, at both the organisational and sector levels. Organisations need to have resources they are able to commit to the process, trust in the relationships they have to other organisations, and a clear understanding of their vision and mission statement. The sector needs good governance structures in place, organisations able to take the roles of leaders and champions, accountability procedures, and the skills to build collaborative capacity between member organisations and in introducing new partners.

The tool can be used at different times in the partnership. Early on, it will provide some information on how the partnership has been established and identify areas in which there is a need for further work. A year or so into the partnership, it provides a basis for structured reflection on how the partnership is developing and how inter-partner relationships are forming. With longer-term partnerships, it may be worth revisiting the tool every 12 to 18 months as a method of continuing to monitor progress and the ways in which relationships are evolving.

The tool may also be useful to a lead agency as a tool for reflection when forming and planning partnerships. Moving forward, we suggest that an organization readiness for change framework be used to explore the need for collaboration, appropriateness – and options as well as sectoral, organisational/individual readiness (competencies).

3. Background to Collaboration

The attraction of collaboration is self-evident. Through collaborative processes and arrangements, agencies tap into the distinctive competencies, resources and connections of partner agencies and through stronger relationships bring collective expertise to bear on ‘wicked problems’, be more productive through greater efficiencies and economies of reduced duplication and finally be more innovative in leading transformational and sustainable change.

The cult of collaboration (O’Flynn, 2009) is also fuelled, in large part, by the policy imperatives and mandates of government officials and the stipulations of their funding allocations as well as need for the NFP sector to remain legitimate to influence decision making processes and funding allocations. So pervasive has become collaboration that it has become an elastic term referring generally to any form of ‘working together’. This lack of specificity about collaboration and its practice means that it risks being reduced to mere rhetoric without sustained practice or action.

Collaboration has been presented as a new and all-encompassing approach to address the myriad of problems and conditions confronting contemporary society. Such a position overlooks both the long history of collaborative practice and existence of a suite of possible integration mechanisms which might equally be applied. Although there is a compendium of terms (Lawson, 2002) this review will focus on three most commonly used: collaboration, coordination and cooperation – the 3Cs (Brown and Keast, 2003).

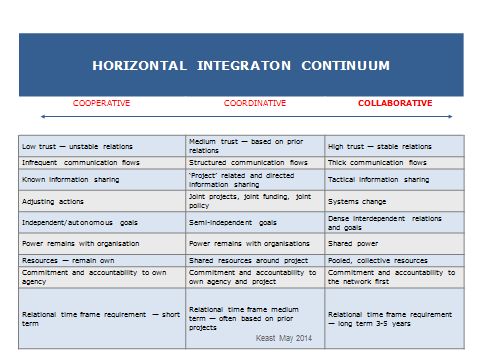

Cooperation, coordination and collaboration are located at different points on a continuum of integrative mechanisms, depending on their level of intensity of the linkages and their degree of formality or informality that that governs the integration activities/relationships (Keast et al, 2007). Based on this, a proposed integration continuum is presented in figure 1 (below).

Table 1: Core Horizontal Integration Relationships

Thus, while these terms, and others as Lawson has defined as the compendium of Cs (Lawson, 2002), are often used interchangeably (Fine, 2001; Szirom, 1998) they are increasingly understood to be analytically distinct (Winer and Ray, 1984; Himmerman, 2002). Your organisation's place along this continuum will depend on the resources you have available and the capacity or willingness to cultivate relationships with other organisations.

3.1. Collaboration

Collaboration is usually the most stable and long-term relationship and is characterised by high levels of interdependency and denser relationships (Gray, 1989; Mandell, 1999; Cigler, 2001). Although all forms of working together require some degree of interdependence, collaborations require reciprocal interdependence. This means that although the actors in a collaboration represent independent entities, they must recognize at the outset that they are dependent on each other other in such a way that for the actions of one to be effective they must rely on the actions of another. There is an understanding that “they cannot meet their interests working alone and that they share with others a common problem” (Innes and Booher, 2000: 7). This goes beyond just resource dependence, data needs, common clients or geographic issues, although these may be involved. It involves a need to make a collective commitment to change the way in which they are operating (Mandell, 1994).

The risks in collaborative networks are very high. Participants must be willing to develop new ways of thinking and behaving, form new types of relationships and be willing to make changes in existing systems of operation and service delivery. This means that the members can no longer only make changes at the margins in how they operate. Instead they will be involved in actions requiring major changes in their operations.

A key characteristic of a collaborative network is therefore that the purpose is not to develop strategies to solve problems per se but rather to achieve the strategic synergies between participants that will eventually lead to finding innovative solutions. In this way collaborating is not about accomplishing tasks but rather finding new ways for developing new systems and/or designing new institutional arrangements to get tasks accomplished. Tasks are still accomplished in collaborations; however the focus is on the processes and institutional arrangement as used to accomplish tasks (Keast, et al, 2007; Mandell, 1994, 2001; Steelman and Carmin, 2002).

3.2. Coordination

The term coordination implies the use of mechanisms that tightly and formally link together different components of a system (Mulford and Rogers, 1982; Alter and Hage, 1993; Metcalfe, 1994; Peters, 1998). Coordination is argued to involve strategies and tasks that require information sharing as well as joint planning and decision-making, joint policy, projects and funding initiatives (Lawson, 2002). Therefore, coordination essentially occurs when there is a need to better align or “orchestrate’ people, tasks and systems to achieve a predetermined goal or mission (Litterer, 1973; Lawson, 2002). As Ovretveit (1993: 40) and others (Litterer, 1973; Dunshire, 1978) suggest the exercise of coordination places emphasis on bringing together interdependent parts into an ordered relationship to produce a whole. In coordination, organisations remain separate from each other (independent) but jointly contribute to an agreed outcome.

According to this view, coordination is not dependent on the good will of the different actors, but has some force of an objective, often a mandate, leading to a more enduring and formalised system of relationships. This may involve adherence to a prearranged plan or formal rules or direction by an independent ‘coordinator’. This potential for an external mandate to drive networked action locates coordination at the fulcrum between horizontal and vertical integration. Since coordination moves beyond information and sharing to the pooled use of resources and joint planning and operation, it requires a higher level of commitment as well as the agreed loss of some autonomy.

3.3. Cooperation

The key element of cooperation is the establishment of short term, often informal and largely voluntary relations between people or organisations (Hogue, 1994; Cigler, 2001). In cooperative relations participants may agree to share information, space or referrals, however organisations remain independent and little effort is made to establish common goals (Mulford and Roger, 1987; Melaville and Blank, 1991). Given that cooperation entails the use or investment of few resources, mainly information sharing, it is also characterised by low levels of relational intensity and risk (Cigler, 2001). In this way, cooperative efforts are centred on establishing relationships with others to achieve individual advancement (Mandell, 1999). As Schermerhorn (in Mulford and Rogers, 1982: 13) notes, cooperation entails the “deliberate relations between otherwise autonomous organisations for the joint accomplishment of individual operating goals”. Thus, it is essentially about taking others into consideration, compromising on some actions without necessarily adjusting individual goals.

3.4. Vertical Integration

The ongoing popularity of collaboration and horizontal forms of integration aside, there nonetheless remains a place for vertical integration. Vertical integration refers to processes that bring large portions of the supply chain not only under a common ownership (e.g. through consortia), but also into one corporation (e.g. through amalgamation or mergers). It may be that after completing this tool you find that the models do not meet all of your organisation’s requirements or reasons for collaboration. If so it may be worth exploring the possibilities offered through vertical integration.

4. How to use the tool

The tool is divided into three sections, the Collaborative Readiness Self Assessment Questionnaire, the Organisational Assessment Questionnaire, and the Sector Assessment Questionnaire. All three questionnaires can be filled out individually or in facilitated groups, the latter option is preferred as working through the questionnaire with partners provides opportunities to discuss issues around collaborative partnerships.

At the end of each questionnaire are directions to either continue to the next questionnaire, or to consider a particular model of networking. Due to the cumulative nature of the resources necessary for collaboration, if you are not able to clearly identify the existence of these resources in your organisation it may be important to consider a less demanding form of networking. It is important to take time at the end of each of questionnaire to assess whether your organisation considers it necessary to proceed.

It is important to remember that collaborative structures evolve over time, growing and receding, depending on numerous factors. Your organisation’s place in the sector may not begin as part of a collaborative core, but rather form part of the broader periphery of organisations, building the relationships and resources necessary to become collaborative partners. Similarly, the organisational culture required for collaboration takes time to develop; it should not be assumed that your organisation can adopt these practices immediately. This is a perfectly reasonable conclusion to reach following this questionnaire, and is the reason we encourage re-examining the tool every 12 to 18 months.

The central questions are formatted for “yes” and “no” answers, with a number of prompt questions to help you decide the appropriate response. It is reasonable to expect that your initial response is more likely to be “maybe” or “sometimes” for many of the questions. In that event, take the time to work through the prompt questions, and discuss with others in your organisation/facilitated group. If at the end of that discussion you are not comfortable giving a clear yes or no answer, the answer is probably no, but you should be better able to identify what needs to occur in order to answer yes in future iterations.

Collaborative Readiness Self Assessment Questionnaire

This is the first of three questionnaires, to find out if you are ready to start the process.